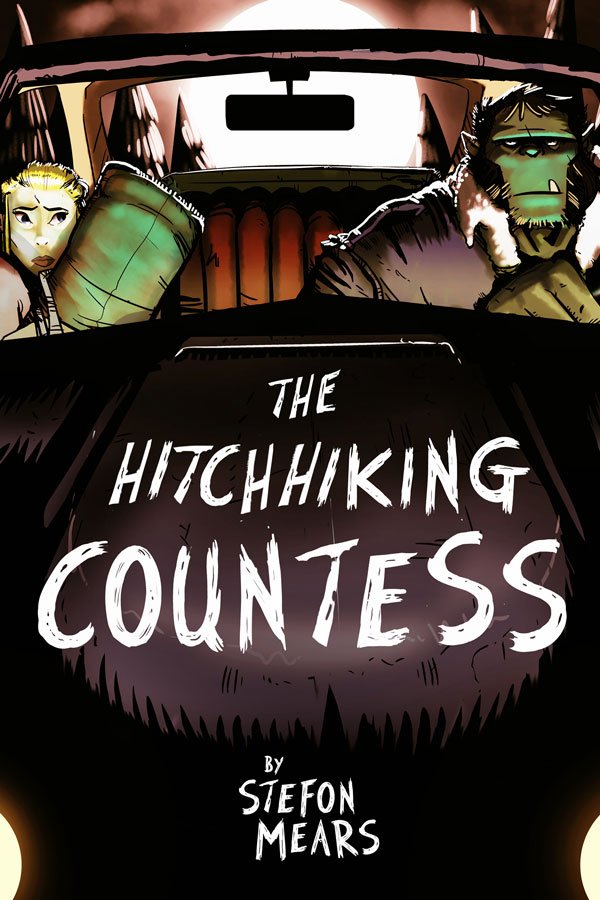

Welcome! This is my monthly free short story page. Every month I will post a new story here, but it will only be up for seven days, so read it while you can!

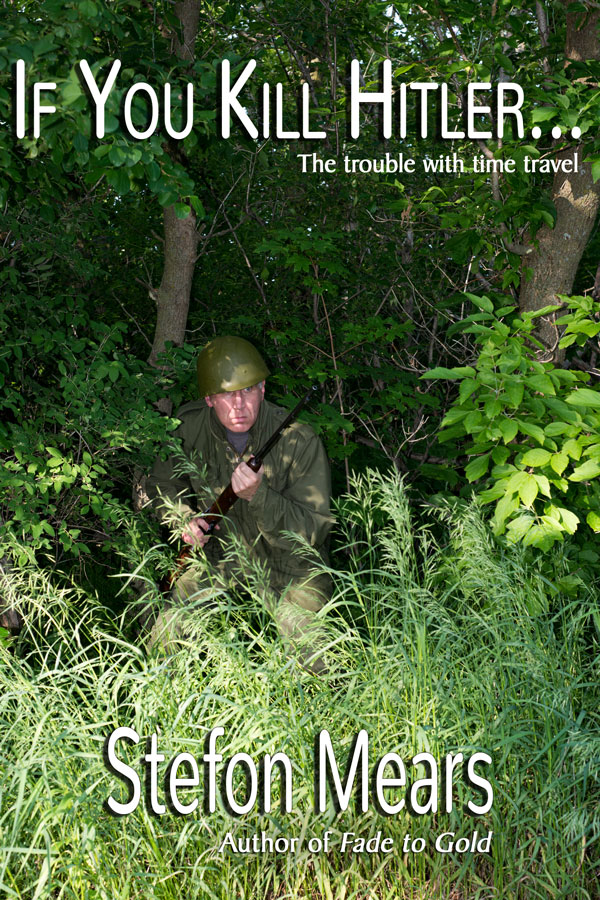

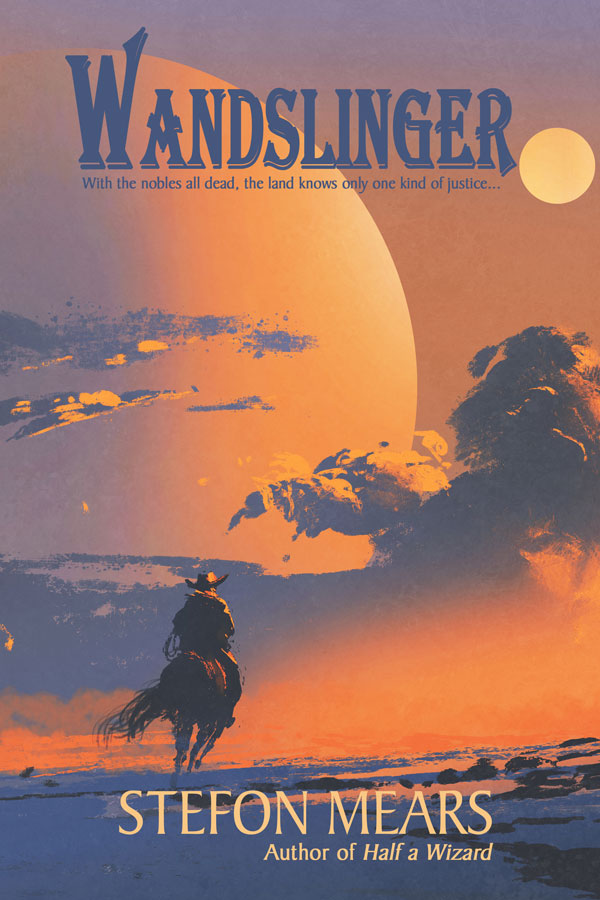

And if you decide you like it and want a copy to keep, click the cover or the links at the bottom to buy a copy of your own.

Goodbye and good riddance.

Gotta be honest here. Nine times out of ten. No. Nineteen times out of twenty I can pick up a hitchhiker and it’s a good experience. I get someone to talk to, they get a bunch of miles closer to wherever it is they’re going. Good all around.

Yeah, I know. “They” like to say picking up hitchhikers is as dangerous as, well, as hitchhiking. Could be some crazy with a knife ready to open a vein or whatever.

Maybe that happens. But it doesn’t happen to me.

Name’s Vic, and I’m built kind of like my Ford truck. Big, green, and bad, with just enough dings and scratches to warn you not to mess with me.

Got a tire thumper under the seat. Just in case.

Never needed it once. Not for a hitchhiker, anyway.

So that night, that was one of the times it didn’t go so well. I was making the long haul up I5 through nowhere California, my truck bed full of…

Look. You’re going to judge me for this. You know it. I know it. But there aren’t that many things an ex-con like me can do, even if…

Yeah, I know. You don’t want the excuses.

I was hauling goblin hides, all right? From the battle lines down around Bakersfield, where they’ve been “incurring” through the Mojave and causing all sorts of trouble.

Anyway, the goblin hides were all sealed in the truck bed, so tight even I couldn’t smell them, and let me tell you I have a good nose for it, same as any other orc.

I was making good time, with hopes of getting to Sacramento before midnight, when the exchange closes and I’d be stuck waiting until noon the next day to turn in the hides. I must have had a good quart of Mountain Dew in me, and enough chocolate that I could still lick the occasional missed bit from the broken tusk on right side of my mouth.

Yeah, just the one tusk, and it’s broken. I’ll never be a glamour boy.

Anyway, I was rocking out to some AC/DC when I spotted the hitcher. Little slip of a blonde, skinny enough to be an elf. Instinct made me want to shoot on past, but my time in the pen, made me double-think it. Seen all sorts in the pen, even had my ass saved by an elf named … well, his full name was way too long for a guy like me to bother with, but he let me call him Flindal.

Flindal was all right. So maybe this little slip of a blonde, she might be all right too.

So I hit my signal like a good little boy and pulled over to the right. Buzzed down the window and gave her the smile I think of as non-threatening.

Well, at least there’s no active menace to it. Many dings and scratches as I have and I can only look so non-threatening, you know?

The hitcher was probably pretty to another elf. Or to a human. Those guys will mate with anything. But to me, she was skinny and pointy with hair so light it looked fuzzy. Like the glow around a streetlamp in a good San Francisco fog. She was wearing brown pants and a forest green shirt, both made from some frilly material probably billed as “softer than air” or “so soft you’ll feel like you’re wearing nothing at all.” All the elves go for that crap.

Give me nice thick jeans and a rough work shirt (black and purple, respectively that night). Heavy work boots too. I like clothes I can feel. If I wanted to “feel like I’m wearing nothing at all” I’d be naked.

But nobody wants that. Not in public, anyway.

She wore her forest green shirt unbuttoned, probably to encourage drivers to stop, but she tied it at her waist that kept it closed over that sickly pale elf skin. Green high-top sneakers. Khaki duffle at her feet.

She was smiling when I pulled up, but the smile died when she saw me.

She got in the truck though, wrinkling her nose at the Slim Jim and candy wrappers, and the empty soda bottles on the floor and the seat. Thought for a minute she might sit on her duffle to avoid putting her fancy posterior on my seat, but she didn’t.

She did lean in for a deep whiff from the pine tree air freshener hanging from my rear view mirror. Must have made her feel at home. She smelled like trees too. Evergreens. Redwoods, plus a hint of sweetgrass. And she probably wanted to get away from the odor of snack food in my truck, and the cow dung from outside.

Or maybe she didn’t want to get turned on by my natural musk. Whatever.

Anyway, she told me she was heading for Dunsmuir. Like I couldn’t have guessed. Big elf contingent around there. All around Mt. Shasta, really.

I told her I was Sac bound, and we figured out where I could drop her.

Stuck up little twig never said another word the whole ride.

Now, I don’t know how many hitchhikers you pick up on an annual basis, but given what I do to make ends meet, I pick up plenty. And they all seem to know that this is a social thing. There’s an expectation of conversation. Humor. Something.

And no, by something I don’t mean sex. Though I’ve been offered a few times.

No, I’m not going to tell you if I ever said yes. Nobody ever confused me with a gentleman, but there are some things I just don’t talk about.

Anyway, this elf twig, this leaf eater…

Sorry. I shouldn’t have said that. Promised myself I’d stop using slurs like that when I made friends with Flindal.

So this elf twig didn’t even share her name. She just sat there silent, big green eyes shining like gemstones as she kept vigil on me or something. One hand in her duffel, probably on a knife. Like she thought I was going to do something to her.

Made me feel bad, at first. I mean, I don’t know anything about this twig. Maybe she’s had it rough as I had. Maybe some orc did something to her. Or maybe to a friend of hers or something. Point is, I tried to be extra soft with my voice, considerate with the music. Tried to put her at ease.

Nothing.

Even though, after a while, you’d think it’d be clear that all I was offering was a ride. And all I was expecting was to be treated like a person. Even conversation about the weather, or where she was going or had been would have done the trick. Anything.

But all she did was sit there, watching me, one hand in her duffel.

I tell ya. The miles couldn’t pass fast enough for me. I even set my cruise control above the speed limit, for once, just to get this twig out of my truck faster. And I don’t like to speed. Cops like to hassle ex-cons, and if the cop were a human, or an elf, or worst of all a dwarf?

Forget it.

And even though she gave me the silent treatment and the danger-eye look, I couldn’t just kick her out. This might have been PTSD or something. Maybe she needed to get to Dunsmuir for treatment.

Maybe I’m just a soft touch, since I got out. I don’t know.

Anyway, the speeding helped shave some of the travel time, and I dropped her off outside a Denny’s in the middle of Sac. She didn’t even say thank you, just waved a little wave as she closed the door.

I couldn’t peel out of the parking lot fast enough.

I was three lights away, maybe a half-mile from the exchange, when I saw it.

Down on the floor of my truck cab, on top of a pile of Snickers wrappers, sat a gold leaf invitation. Literally. It looked like a huge, gilt maple leaf.

I sighed as I picked it up.

Blah blah blah invitation blah blah blah bearer admitted to blah blah blah elevation of Countess…

Crap. This was politics. And important.

And my night just got a lot more complicated.

#

For a fleeting moment there, I was tempted to toss that gilt maple leaf out the window of my truck and forget about it. Not like I owed the little twig anything. She didn’t even have the decency to make conversation.

Couldn’t do it though. Any more than I could have kicked the little elf twig out of my truck back when it was clear she had no intention of being social.

But that invitation, it must have been in her duffel. That meant she was important enough to rate a personal invitation to the elevation of some elf countess. No idea why she was hitchhiking unless…

That was when it hit me. It hit me so hard I missed the light change and three different horns had to bellow at me to get me moving again.

That elf wasn’t just anybody. She was Somebody. And a Somebody doesn’t hitchhike – unless that Somebody’s been ousted. Outcast. Kicked out on her tiny little patoot. Maybe by the former Countess Whatever. No friends. No resources. Just somebody on the inside – possibly another Somebody – who cared enough to send her the invitation.

Or mocked her by doing it.

Maybe knowing she had no way to get there.

Maybe knowing she had no one to help her.

I knew just what that was like. Hell, every ex-con knows. We’re social lepers, and everyone assumes each one of us is a robber, a rapist and a murderer. Even a guy like me, who hasn’t done any of that.

The little twig had guts enough to go back to the place that kicked her out. And damn it, I had to help her do it.

I confess, though. I swung by the exchange and turned in the goblin hides first. No good running around being noble if I starved to death in the process.

Unfortunately, that cost me time. Time sitting fifth truck in line, waiting while the orcs and humans in blue State Police unis did their counting and checked IDs and all that stuff. Then checked them again before they paid out.

Didn’t get out of there until after midnight, a good hour after I arrived and maybe an hour-twenty since I dropped the elf twig off at that Denny’s.

She was long gone when I got there though. Joint was mostly empty. Just three dwarves in a corner booth, slumming with cheap beers, and a human couple at the counter. Younglings, I think, and more into each other than their food.

Had to ask about her at the counter. Asked some old human woman, built solid enough to be an orc, but with the wrinkles and gray hair that humans get as they age. Name tag identified her as Mabel. She smelled like eggs and maple syrup, and my belly rumbled that candy wasn’t enough to sustain a big guy like me overnight.

But I’d wasted enough time already.

“Seen a little elf twig around here?” I asked. “Skinny thing? Blonde hair, khaki duffel? Looking for a ride?”

“Oh, yes,” Mabel said, with that dreamy look humans get when they talk about elves. Like they burp dreams and crap fairy dust or something. “Beautiful as a fairy princess, that one.”

Then she got a better look at who was asking, and the dreamy expression faded to a nightmare of suspicion.

“But she’s long gone by now. Maybe halfway to Tahoe. Boyfriend picked her up. Had a warrior look to him, like he’d been fighting down in the Mojave.”

“Look,” I said, holding up my empty hands and trying to look non-threatening for what felt like the ten millionth time in my life, “I don’t want trouble. For me or the elf. I just—”

“Just what, Greenie?” called one of the dwarves from the corner.

I didn’t have to look over to know they were getting out of their booth. I could practically smell the cheap beer from here, which would give them the excuse to act drunk, even if no dwarf could get drunk off the beer they served in a place like this.

I focused on Mabel, even though she turned from the cash register area of the counter and picked up a coffee pot like she had a full house to check on.

“I’m the one who gave her a ride here from down south of Los Banos. She dropped something in my truck and she’s going to want it.”

“Mabel said she’s gone, Greenie,” said another one of the dwarves. As soon as I heard the fake Scottish brogue, I hung my head forward. These three were definitely looking for trouble.

Despite what movies may have told you, dwarves aren’t Scottish. In fact, most of the dwarves I’ve been forced to deal with have the same accents you’d expect, depending on where they’re from.

But when they’ve had a few, and they’re looking for trouble, they all start sounding like rogue highlanders or something.

“Just tell me what you can about the guy and car she left with.” I was pleading with Mabel now. “I’ll handle the rest. Believe me, what she left behind she doesn’t want to lose.”

“Give it to us then, Greenie.”

I had to turn around and face them. Three dwarves, all so young their chocolate brown beards weren’t more than scruff. Let their hair grow long enough to braid down their backs. Smooth skin too, and tanned. Like they’d never seen any kind of real fighting. Only one of them had the kind of heat scars that came from a forge. Gods only knew what the other two did for money.

“It belongs to the elf. I’m getting it back to her.”

“Expecting a reward, Greenie?” This was the one in front. The one lightly scuffed from working in a forge. Obviously their leader. “Hand it over and we’ll give you the reward of letting you walk out of here.”

My mouth started watering. Not the hunger-watering, you understand. But orcs, we all love fighting. It’s who we are. It’s in our blood. Truth is, fighting is when we come closest to the gods. I’ve only ever felt at peace when the adrenals are kicking in double time and my heart’s pounding and I’m tasting battle-saliva and…

There were only three of them. Not one had the scars to be warriors. Hell, I had more scars on one arm – either arm – than all three of them put together.

They didn’t know how to position themselves. Packed in tight, triangle. I could smash into the leader and bowl all three down onto the thin carpet. Hard floor underneath, too. Maybe slam their heads together on the way down. Maybe bite off a nose while I…

“Call the cops, Mabel,” I said, reminding myself it was the battle saliva I was tasting, not dwarf blood. “I’m being threatened with assault and battery. And robbery, for that matter.”

“Yeah, Mabel,” said a dwarf from behind the safety of his leader. “Call the cops and arrest his ass for robbing an elf.”

“Shut up, Loni,” said the leader, but he kept his eyes – and his next words – on me. “What’s the matter, Greenie? Too chicken to fight? Afraid we’ll spill all your smelly green blood?”

I snapped at him before I could stop myself. I only have the one tusk, but my teeth are as big and strong as any other orc’s, and when they clack together that way the sound rings out.

Thin wooden partitions behind the dwarves, but nice wooden benches for people to sit on while waiting for tables. Perfect for cracking dwarf heads on. For jaw stomping. For…

I clenched my teeth and growled. “Call them, Mabel. Please. I don’t want to wreck your place.”

I was getting jittery though my knees. My hands formed fists when I wasn’t paying attention. All my muscles were rippling the little series of clenches to loosen them up and speed the distribution of blood and adrenaline.

These dwarves had no idea what would hit them.

I could kill all three of them before any of them could land a blow.

“Please,” I growled.

“Riok! Loni! Dur! Back to your table right now or you’re banned for life.” Deep voice from this one. Definitely not Mabel, but I couldn’t turn to see. Fortunately that was when the older dwarf stepped between us.

Now this dwarf could be trouble. Older than the other three combined, and he had the same kind of scars I did. Battle scars over rough skin and corded muscle. Rough jeans and work shirt too. Bald head, but a long red bead.

“Make me say it again and I’ll tell your parents as well. And knock off the fake brogue.”

The new dwarf turned to me and sized me up at the same speed I’d gone over him. He nodded.

“Thanks for holding back. Mabel, get this fine orc a full to-go cup of my own espresso, and a mini pecan pie on the house.”

I nodded, respecting the dwarf twice as much now, for obviously knowing the right combination of sugar and caffeine to bring an orc down from a battle high.

“So,” said the dwarf, “the elf you’re looking for is gone. Good of you to try to get her back her … whatever it is. I don’t know who she left with. What about you, Mabel?”

Mabel shook her head as she handed me the mini pie and the espresso, and I downed them both at speeds that drove the dwarf’s bushy red eyebrows high enough to masquerade as hair.

“Thanks anyway,” I said. “I know where she’s headed. I’ll just have to try to meet her—”

“I saw,” said a small, high voice. The female of the two human younglings. I’d forgotten all about them. “She caught a ride from Clem in his cherry ’68 Mustang. Said yes before I could warn her. And if I know Clem he’ll have a side-trip in mind.”

“You’re sure it’s a ’68 Mustang?” I said. She nodded. I smiled. “Then tell me about this side-trip and I’ll take it from there.”

#

Orcs like to brag about a lot of things, but one thing we keep to ourselves is our sense of smell. Truth of the matter is that our noses are as keen as those bloodhounds that humans keep. It’s the real reason we’re such good hunters.

Now, I knew the elf twig’s scent. No way I could spend that much time with her in my truck and not get a solid sense of her particular blend of redwood, sweetgrass, and the tang of cow dung that caught in her clothes while she waited for a ride.

The problem was that I didn’t spend a lot of time around elves. Well, normally that’s not a problem for me or them, but at that moment it was a problem because it meant I didn’t know how much of that smell was her and how much was just, well, elf. If I went on the scent I thought was hers, I risked accidentally following the scent of another elf.

But now I knew to go from the elf smell that combined with the particular combination of odors that made up a ’68 Mustang. For the olfactorily impaired among you, let me explain. No two types of cars burn their gas and oil in exactly the same way. Tires vary, as do seat covers, but the tang produced by the way a given make and model burns oil and gas is as distinctive to an orc nose as a fingerprint is to the eye.

So I was back in my truck, driver’s side window down, and following the combined scent of elf and Mustang.

Just on the outskirts of Sacramento, going north, was a rest stop on I5. Seemed silly to me to put one that close to the freaking state capitol, but then, no one asked me.

According to the human youngling female, “Clem” liked to take girls there. Terrible thing to do, if you ask me. Offer an elf a ride, then stop someplace like it’s a date.

But, again, no one asked me.

So I followed the scent onto the freeway and north. And sure enough, no more than a handful or miles outside of Sac I caught the scent taking an exit. To a rest stop.

Class act, this Clem.

The rest stop looked like someone put a parking lot inside a forest. Redwood trees blocking it from the road, and my big Ford pickup felt small alongside these behemoths as I pulled in.

In the center of the parking lot was a big bathroom area. The kind with showers as well as toilets. Concrete with gray paint and a red tile roof. Males on one side, females on the other. Along the front, a series of vending machines for snacks, sodas, coffee.

Down at the far end of the lot were a herd of mobile homes, from the little ones that looked like someone dropped a tiny house into a truck bed to the big ones that could have housed a family of fifteen.

On the near side were a handful of cars, as though the cars and the mobile homes had to run in separate circles. Huh. But the smell led the way and in a few moments I was parked behind the Mustang – with its doors open – and jumping out of my truck with my tire thumper held tight against my thigh to avoid drawing attention to it.

I said I never used it on hitchhikers. I didn’t say I never used it.

The car, of course, was empty.

That was when a scream pierced the night. High and clear, like the voice was made for singing, not screaming.

Then again, I didn’t like to think anyone’s voice was made for screaming.

I started running flat out toward the scream. It came from somewhere down by the mobile homes, and sure enough, with every inhalation I could pick up the elf’s scent. And another scent I’d picked up along with the elf and the Mustang. Human. Male. Young. And that herb some of the humans like to smoke. Spot, I think they call it. Under that the oily greasy odor humans get when they don’t wash for a few days.

Had to be Clem.

My work boots were pounding the asphalt like my fists were going to pound this jerk’s face – fast and heavy. If I got the chance, that was. I mean, a scream like that – gotta pull people out of their mobile homes, doesn’t it?

Yes and no, it turned out. Yes, it inspired them to action. But no, the action wasn’t helping. Instead, mobile home engines fired up, and their drivers started spinning tires like me pulling out of that Denny’s earlier.

I never slowed up.

The scream came again. A word this time. “Help!”

This time I was close enough to hear more than that. A human male voice, saying, “Come on, baby. Don’t pretend you don’t know about the ride tax.”

Ride tax? Now I really hated this guy. Giving those of us who pick up hitchers a bad name.

I was close enough to see them now. In the orange sodium light, which probably made me even scarier to look at. I mean, orange and green? Even I didn’t like that combination.

The elf twig had one arm clutching her duffel bag in front of her, her other arm extended forward, holding a wicked-looking dagger. Her shirt was open, so the duffel bag was shielding her modesty as well as her flesh.

Clem had his hands up, like he wasn’t offering any threat, but the rest of his posture told the truth. His knees were bent, lowering his center of gravity. His elbows were bent. His weight slightly forward.

She heard me coming before he did. Elf ears, you know. And I damn near turned around when I saw her jerk the knife back and forth like she wasn’t sure which was the bigger threat.

Clem looked too, then, and he had no doubts about who the bigger threat was.

“Whoa!” said Clem.

Shoulder, meet gut.

I plowed into Clem at full speed, but damn if the boy didn’t have some moves. He managed to spin us in the air so that it was my heavy green butt coming down hard on that asphalt.

Mom always warned me that the gods don’t smile on people who do good things for unselfish reasons.

Only my love of good, strong fabrics kept me from losing inches of green skin when we crunched and bounced on the asphalt.

Clem wasted no time in punching my rib cage. Idiot. Probably hurt his hand as bad as he hurt me. I slammed my tire thumper just under his rib cage and watched his eyes go round as the air whooshed out of him.

I toppled him over, pulled him up by the collar of his AC/DC tee shirt – just one more thing to piss me off – and punched him five times hard in the face. Broke his nose and bruised him up pretty badly.

After the fifth punch, a line of bloody spittle dripped from his lips and I figured enough was enough. I spat some of my battle saliva in his face and said, “The ‘ride tax’ is a lie invented by assholes like you.”

I dropped him and stood up. The twig was gone.

I sighed, then felt a moment of panic that she’d drive off in the Mustang and forget about her invitation. A quick pat of Clem’s pockets reassured me that he had them still.

I looked around into the trees, but if she got in there, I’d never spot her. Spotting an elf among trees was worse than a needle in a haystack.

I was tired. The whole back of my body hurt. And my belly was rumbling that the pecan mini pie and extra-large cup of espresso had been used up. I did not have time for this.

“Hey,” I yelled. “Hey elf girl. In case we all look alike to you, I’m the orc who was kind enough to give you a lift up here from Los Banos.”

Nothing. Not sure why I expected otherwise.

“You dropped that invitation of yours in the cab of my truck. And believe it or not, I’ve been hunting you down to give it back to you.”

Still nothing?

“Fine. Hell with this. The invitation says it admits the bearer. Maybe I’ll show up myself and see how the elves party.”

She melted out of the trees to stand in front of me. Seriously. Like one minute there was nothing but shadows and redwoods, and the next here’s the twig, melting into shape with her duffel bag hanging off her shoulder.

And her shirt hanging wide open.

I averted my eyes, out of politeness. Not that there was much to see. Honestly, how do elves manage to feed their young with those things?

She laughed as she re-tied her shirt, and the laugh was the most pleasant sound I’d heard from her yet.

“Truly?” she said. “You not only sought me out to return my invitation, but you avert your eyes from the sight Clem fought so hard to see?”

“Look,” I said with a grimace. “I’m nobody’s idea of a hero, all right? It’s just … I know what it’s like to be the outcast. To have nobody on your side when you need it. I’m betting that invitation is your chance to come back from that. To be Somebody again.” I shrugged. “I don’t know.”

“Thank you,” she said. And then she gave me her name, but no way I’m going to remember that whole thing.

“Mind if I call you Hirala?” I said, sticking to the first three syllables. “I’m Vic.”

“I would take it as an honor, Vic,” she said.

“Then let’s get moving before some cop comes rolling past and decides to play blame-the-orc.”

#

She was chatty now, this Hirala. Like she hadn’t had anyone to talk to in twenty years, and she wanted to get everything out at once. I didn’t mind, though. Made me feel better about picking her up.

If I followed it all right – and I’m not sure I did because elf politics are pretty complex – she might be the proper heir to the county, depending on about three factors that no one could judge until she got there. She was kicked out some twenty-five years ago by the then-current countess who wanted to improve the position of her favorite.

Anyway, the story took the rest of the way to the rest stop just shy of Dunsmuir, where she had me turn off.

This rest stop was tiny, compared to the one outside of Sac. More trees, fewer spaces, and no way that tiny bathroom building had shower stalls. The place barely had two vending machines, and the soda one was off-brand.

And all the parking spaces were empty. For an old road hound like me, that gave me the creepy chills coming up the back of my neck. I’d never seen a rest stop empty. Not completely.

I found out why when I angled for a space.

“No,” Hirala said, directing me instead to the footpath.

I questioned her twice before my truck reached that footpath, but she insisted, so I persisted.

The moment my tires touched the footpath, it widened to three times its width and suddenly the redwoods above us had branches curve together to form a tunnel lit by fireflies bigger than my fist.

I kept a slow, smooth roll down the tunnel. Elf magic gives me the creeps. They act like its natural, their “Art,” but give me blood and bones and dirt any day.

We reached the other end of the tunnel, where two guards were waiting for us. Tall and slender, but fierce-looking in their bright, shiny silver armor. Plates of it and greaves and all of that stuff, with helmets adorned with the likenesses of falcons on top. Shields on their arms that looked like they could stop my truck.

And very long swords in their hands. Swords that glowed bright red and pointed my direction.

“Whoa, boys,” I said, hands coming up once more as I stopped the truck. “I’m just the driver, and we have an invitation.”

Hirala held up the gilt maple leaf, and when she did the guard on the right gave her this intent look, then tears started trickling from his eyes.

He said her entire name in less time that it takes me to say mine, and he made her name sound like a song.

Suddenly the rapid elvish is flowing from all three mouths, like competing bird songs. And the guard who knew Hirala was opening her door and she was getting out.

“Hey!” I said, finally shutting them up and drawing their attention back to me. “Where should I park?”

Nobody can look down their long, thin nose like an elf, and the two guards reminded me of that.

“Park?” said the one with his hand on Hirala’s shoulder in a way they were both comfortable with. “Why should you need to park?”

“Yes,” said the other. “You can’t imagine you’ll be allowed to stay for the ceremony.”

“Especially since…” and he continued in elvish, as though the words were too important for the likes of me.

“Hey!” I called again. This time, Hirala answered.

“Thanks for the ride,” she said. “This is my stop, and I guess you better get going.”

And she turned her back on me. Her friendly guard closed my passenger door, still streaming songlike words at her nonstop. The other guard stepped up to my window.

“We’re not going to have a problem, are we, orc?”

I could taste the battle saliva starting again. I couldn’t believe the nerve. After all I went through to get that little leaf— twig of an elf here to get dismissed like a servant. I clenched my jaw to keep it from snapping at the elf guard.

“No,” I said, and I put the truck into reverse. “We won’t have any problems. Elf.”

I turned the truck around and drove away.

I didn’t need the aggravation anyway.

<<<<>>>>

And if you missed the last few, you can get them here…